The Body in Pain

The Making and Unmaking of the World

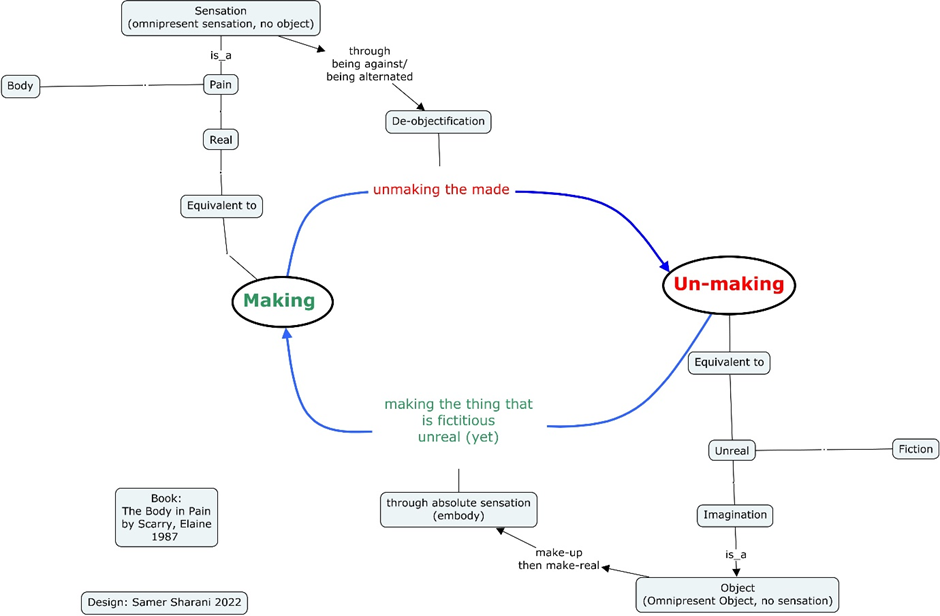

The central notion on which this book dwells is the eternal transformation between making and unmaking of the world in which we live. It is the human capacity, and maybe fate, which steers human beings to make the reality, the objective reality, the sharable realm, the tangible, and then to unmake what they made, receding it to fiction, the unreal realm, the imagined, the intangible that is we cannot grasp in our sensation. And again, from the realm of fiction, we, human beings, are steered again by our capacity to embody the imagined, the fiction, so we make the “unmade,” giving it a body, turning it into a sharable world. The cycle continues infinitely (see illustrative figure. 1. If the photo is not clear, click it here).

Why does this cycle exist?

Or how does it work, how does it exist?

Its “making” wing is the real world in which we can see each other,

share common sense, touch tangible objects, and talk about things existing

there in this real world. The absolute “nature” or the absolute value of this

“real,” of the making wing, is body. My body is the closet tangible and real

thing or object that I can recognize and sense. Without my body, I cease to

exist and so does the world. The body, in turn, reaches or materializes its

infinite nature, the extreme value, though pain. Why? Every sensation,

feeling, or recognition has an object against which this sensation impinges.

You love someone, you hate a type of food, you are afraid of a thing, and so

on. You are in pain of … nothing. Pain has no object onto which it can hinge.

Pain is objectless. It is a mere, absolute sensation, it is an absolute feeling

that is generated from the body without any object. Hence, a body in pain is an

absolute sensation; it is the most real because it does not need any other

object to feel its pain.

Pain is not sharable at all. It resists “verbal objectification”

(p.12). How can you share, really share, something that is objectless? In order

to share your pain with others you have to create an imagined body: when you

have a pain, what causes the pain is your body itself; if a nail penetrates

your foot, the pain is caused by - firstly - the nail and - secondly

- (i.e., more closely to the real cause) by the body itself. Pain has always a double

agent causing it: the trigger (fever, nail, lashing, etc.) and the body

itself. So, saying that what causes a pain is a nail entering my foot is not

sharing. You have to say I feel pain because a nail entered my foot and my body

hurts my body. A listener should imagine a body, his body, experiencing a

nail entering its foot, then causing pain similar to what you say. He or she

can imagine a nail penetrating a foot, but it is impossible to interiorly

incorporate an image of a body (another body) hurting even if the listener had

a previous close experience. Pain is objectless, so it is timeless. You cannot

share it with other. But it is really here, I feel it, my body in pain, and

this cannot be more real. Pain is the most real thing that I, as a person,

experience. But I cannot share it with others. That is why pain constitutes the

extreme value of the body: It makes it the extreme real, but “unfortunately”

non-sharable. The absolute real, seemingly, is escaping the world of reality,

the tangible; it roams around the edge of this reality. It is able to flee the

realm of “making.”

This absolute reality, the absolute real, the omnipresent sensation

that does not need an object to be (because it is so much real) now escapes the

real realm, the making wing of this cycle, and enters the world of fiction, of imagination.

The world of imagination is unreal. It is a fiction. Imagination

consists of two stages: make-up and make-real. Making-up is to start coveting a

fiction, a thing that does not exist (otherwise it is not a fiction); this

thing, which is to be imagined, cannot be seen by me, a human being who is

calling it to come. Imagination in its deepest nature is an object that cannot

be seen yet. Think of it in this way: You need to create a “thing” (a

painting, poetry, a novel, a vehicle) that is absolutely fictious, then it must

have never existed before; i.e., it must

be unreal. Nevertheless, it is a “thing” to come, you know it is a thing, but

you cannot see it, you cannot touch it, you cannot yet describe it.

Hence, imagination is, contrary to pain, only an object, an absolute object

that is not seen yet (while pain is an absolute sensation that has no object).

We cannot stay in the realm of imagination, unrealness, the

unmaking wing of the cycle, so we have to give a sensation to the object we are

trying to imagine, to create. We embody it. This is the second stage of

imagination: make-real. We give the imagination a body that we can see. We

make the “unmade.” So, we again enter the wing of “making.” The cycle

continues in this manner.

This cycle is our nature as human being on this earth. Based on it,

this book explains torture and war. Why do wars happen? Why do we torture

others?

Both of torture and war are functions of fiction. Torture’s

motivation is only masqueraded by information extraction or punishing a

prisoner, but fiction is what engenders our ability to torture. War is not

national defense, nor is it nation-recreation, it is the capacity of fiction

that pushes us, as human beings, to war.

Torture

Torture means inflicting as much as possible pain to a body.

Torturer pushes the pain in the body to its extreme level; hence, he pushes it

towards the edge of unreal. Torture unmakes the made, it unmakes the body. It

transforms the body from the making wing to the unmaking wing as the motivation

of fiction nourishes a torturer to do so, or the capacity of human beings of

fiction, or unmaking the made, ignites a torturer to push his prisoner’s body to

the edge of the unreal, unmaking it. Let us explain more.

When a prisoner is tortured, pain is exacerbated. The body, as we

said, reaches its extreme value: Now it is the most real thing, only pain

exists, only pain is generated from the body, and the limits between the

existence, the universe, and the body cease to exist. Either the body becomes

the universe or the universe shrinks to be the body. I am tortured, so I am in

a huge pain, my body is really, very really, here, it tells me through pain how

much it is real, but I cannot share that with others. In the extreme pain, the

world ceases to exist, nothing but my body exists. The Self, the voice, the

objects cease to exist. Only my body in pain is here. My body is absolutely

here and is absolutely absent from others, from the sharable world. Then the

body deteriorates to be nothing, to be unreal, to enter the realm of fiction.

How?

In torture, my body is what hurts me, my body is against me. The

torturer is only the first agent of pain, but it is my body what hurts me. I

become against me. This is self-annihilation. Moreover, in torture

everything that the civilization has made is turned into a tool for torture

(e.g., electricity, even doors are used to hurt your fingers). The “made” by

civilization participates in torture, in annihilating the body; therefore,

torture is “the de-objectifying of objects, the unmaking of the made” (p.41).

Objects cease to exist as they are made (a door is no more a door, but a tool

for torture). This completes the transformation from the making wing to the

unmaking. Everything is de-objectified; everything is fictious now.

According to that, if a

prisoner confesses, that does not mean anything. In pain, the voice ceases to

exist, the world ceases to exist, so a prisoner does not really confess. He

cannot. He loses his voice, he loses the world on which he can make a

confession about. The torturer, himself, ironically does not usurp power as he

tortures the prisoner more and more because as more he inflicts pain on the

prisoner’s body, the body and its world and voice cease to exist. The

torturer usurps only absence. Pain in its extreme value unmakes the objects

of sensation. Power becomes naked with no object.

War

“[I]t is when a country has become to its population a fiction

that war begins […] ” (p.131, italic in origin).

War is not waged for national defense, at a fundamental level, and

it is not a way to recreate the national self, but war is a “fiction generating”

capacity (p.142). Similarly to torture (to some extent), war is a function of

fiction, to generate fiction, and then, as it ends, to make this fiction real.

How can we understand these blurry ideas?

Let X and Y be two nations. Each one of them has a self, an identity,

an understanding of itself and of its ideologies as real. For a nation, the

self, the ideas, etc. are real as much as a tree and a mountain are real. When nation

X and Y start to de-real each other, when they begin to uproot the self-perception

of each other from its realness, showing it as unreal, as illusions, then they

start the war. They start the war because the two “reals” are conflicting each other,

and only one can survive, whereas the other is thrown away as unreal.

However, as war erupts, fiction is generated, not the “real.” The real

is only to be born or carved out after the war’s end. In torture, the

body ceases to exists, and so does the world and the voice, and only the

sensation without any object prevails. In other words, what is real parishes forever.

In war, the “real” ceases to exist as the fighting nations “de-real” each other,

but only temporarily; the real is succumbing into the unreal/unmaking during the

war. After the war ends and when a victor or a “peace” stands strongly and proudly

again, a nation re-establishes its real and de-“de-real” the war. In other

words, after our war, we make the “unmade,” embodying the fiction again.

X and Y nations fight. During the fight, they de-real each other.

When X wins, it makes the fictions (that were generated at the dawn of the war

and during the war) real again. It becomes its own real that Y cannot de-real.

Nevertheless, war itself is a function of fiction; it leads to the

wing of unmaking. Each warrior justifies his fighting by three themes: “I kill”

– “I die” - “for my country.”

I Kill

I kill the other, the enemy, another human being, and I kill or get

rid of buildings, roads, dreams, and so on. This first action of war does not

build anything. It is totally and essentially nihilism-producing. I, as a soldier,

kill, so I produce vacuum. I produce nothing. This is not enough to make me fight.

No one wants to be nihilism-generator. Therefore, I, the soldier, add another

theme: I kill “for my country.” Then the killing I do does not generate

nothingness for the sake for nothingness, but it does so for giving “my country”

a chance to survive, to exist. Hence, my action of killing does not totally

fall into nihilism, but it creates, it makes something real, which is my country.

Now, let us compare two actions: greeting your friend in a street and killing

in a war. The former’s meaning is interior. You greet someone, so the meanings

of love, friendship, and amity emanate from this greeting itself. The greeting

is enough by itself to generate these meanings. Killing’s meanings, on the

other hand, are exterior to this action. I kill someone, but this action does

not generate the meaning of whatsoever by itself; I need “for my country” to

make the action of killing meaningful. The meaning of killing is exterior.

The action of killing, therefore, does not provide me, the soldier, with

stability. It does not serve as a referential point on which I can

trustfully lean. “To kill” does not make me sure of my existence, of my

realness.

I Die

The second theme is “I die.” I go to war to fight and die. When I

die, a citizen of this nation (my country) ceases to exist. I die, so there is no

more “my” country. Indeed, a nation is embodied in its material citizens’ bodies/body;

hence, the action of “to die” in a war is essentially against the notion of the

nation! “To die” unmakes the nation. It gets rids of the national body. Again, “I

die” does support me with a stable reference in which I can plant my meaning.

For My Country

The third theme is “for my country.” Even this theme is not enough to

serve as a stable reference of the Self that is engaged in war. As war ends,

peace (whatever type of peace) follows; this peace generally includes the

others whom I, the soldier, was fighting. They can become citizens in “my

country,” they can become my comrades in the army after they are defeated. A

new constitution can be written, and the enemy is suddenly not enemy anymore,

its killed soldiers are not deaths but victims of atrocities. “My country” for

which I die and kill will be conflated with the enemies. In sum, war produces referential

instability (p.121). This referential instability is the sign of war-as-unmaking

or of war-as-fiction-generating. Fiction and unmaking produce the “unreal,” as

we said before, and the “unreal” has no reference. Unmaking and imagination

lack sensation that can distinguish between things because there are no things

in the pure imagination and the pure-unmaking, there is only omnipresent object

without sensation. No things/objects, no reference.

Notes about Making

Making and unmaking are two entangled wings of our capacity as human

beings. Pain is the extreme and the most fundamental real “thing” that exists; that

is, it is generated in the body, making the body the most real ever, but without

an object. Pain then provides us, we the human beings, with the absolute sensation.

The absolute realness. Unmaking is the absolute object that lacks body or lacks

sensation. It is unreal. It struggles to be. Hence, imagination provides us

with Wish. This wish does not revoke an image of something; it is not an

image of your lover that you remember/miss; rather, it is the image of the absence

of your lover. Your lover exists no more, so you wish her/his existence. Wish

is the 2-D image compared to the absence of an object not to an object.

Wish and body have to meet. That is how making and unmaking are

transforming to each other (p.164). The result of their meeting is objects

or Artifact. Artifact, what we make, is born from the Wish’s need

of a body and the body’s needs of a wish. Wish needs body to be seen. Body

needs wish because the body actualizes its extreme value only by pain. Pain

should vanish (of course it must! It is pain.) How? By making it unreal. “[A]rtifact

is a conflated projection of the fact of physical pain (our body) and a

counterfactual wish (our gods), that itself makes the realness of pain unreal

by making the unrealness of the wish real (embodied)” (p.292, emphasis

added).

So, we live in the Artifact that is swinging between making and

unmaking. The relationship between human beings and the Artifact is double-folded

in nature: on the one hand, it is a projection as human beings, the

makers, make the artifact, and ensure the embodying of the Wish into the Body;

and on the other hand, it is a reciprocation, as the Artifact impacts

the makers, the human beings, and reshapes them. Reciprocation is well

expressed in this quotation: “[T]he object [or the artifact] is only a fulcrum

or lever across which the force of creation moves back onto the human site and

remakes the makers” (p.307).

(Note: Politically speaking, liberalism can be framed as an

ideology focusing only on the projection type of the human-Artifact relation,

whereas communism focuses solely on the reciprocation relation.)

Two large Artifacts have dominated our life: God and the collective

economic system. God is the Wish that we have embodied in religious narratives.

God penetrates our body, the human being’s body, and exists through pain: punishment,

Christ/Cross, original sin, etc. All of these painful narratives have been created

to give God, the absolute Wish, the absolute imagination, a body. Pain is

chosen as the gate for God to enter the body because pain is the extreme

real experience someone can have. The collective economic system is similar. We,

the human beings, the makers, have made this huge system to embody our Wish into

money, production, and so on. So, the projection type of the human being-Artifact

manifests through God and Economics. However, the problem lies in the other nature

of this relation: reciprocation. The Artifact (God or Economics) does not reply

to its maker. God has never answered our prayers, nor has the economic system

made us equal or safe. The relationship between the Artifact and its makers is

imbalanced. What makes this problem worse is that the maker, the human being,

cannot stop producing the artifact or sustaining the projection relation with it.

This is the source of our suffering. “[T]he large Artifact (God in one, the

collective economic system in the other) continues to be a projection of human

capacities but has ceased to perform the counterpart of projection,

reciprocation: God does not answer prayers (the peoples' voices are heard

instead as godless murmuring and complaint); the economic system does not warm,

clothe, and feed (the peoples' voices are again heard as murmuring and

complaint rather than as an announcement from the creators themselves that a

problem in the interior structure of artifice has arisen)” (p.276).

In these paintings (Paintings by Millet. Source: Wikipedia), below, the book argues, we can see how the maker is melted with the Artifact. The bodies of the women and the man are almost melted in the environment where they work. In other words, the artist consciously or not expresses this “reciprocation” between the maker and the Artifact by melting the body’s boundaries with the environment.